This week I’ve been writing about musical time and how it is shaped.

In “Hearing Musical Time”, I discussed how a drummer’s shaping of time imbues the whole ensemble with a particular personality. In “Hearing Musical Time Part 2 — Three Springsteen Drummers,” I compared the different sides of Bruce Springsteen brought out by drummers Vini Lopez, Boom Carter, and Max Weinberg.

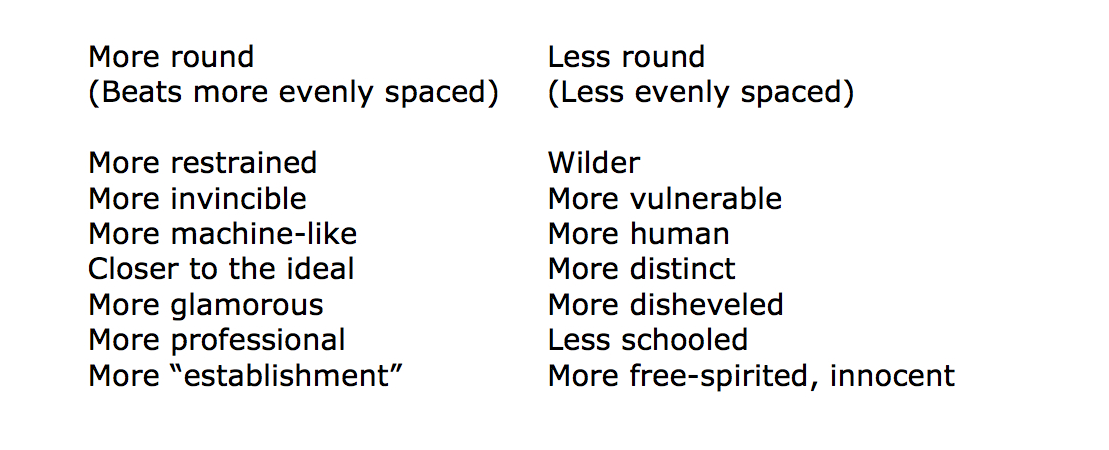

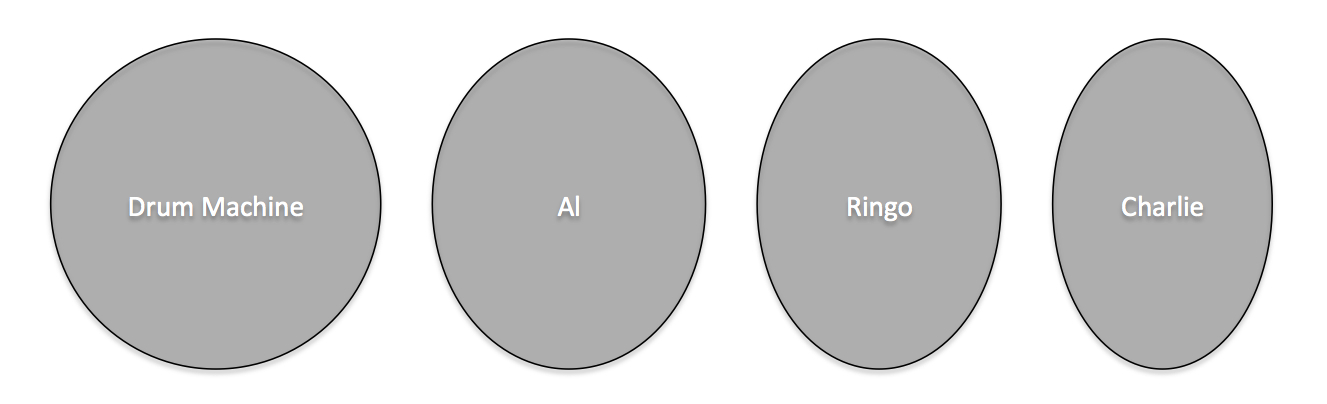

In this post, I’d like to try something similar with two drummers who played with John Coltrane—Elvin Jones and Roy Haynes. We’ll have the advantage of being able to compare them playing the exact same song, “My Favorite Things.” In earlier posts, I’ve focused more on differences in the shape of time and suggested that evenly-kept time resembles a round wheel and uneven time-keeping resembles a more misshapen wheel. We’ve heard how the variety of shapes creates interesting possibilities.

Here, I’d like to focus more on the texture of a drummer's timekeeping. On these two recordings, Elvin Jones and Roy Haynes create radically different textures that make a bit impact on the ensemble.

Before listening, we should note that many of the differences between these two recordings stem from the fact that the first is studio recording and the second is a live performance (and live performances are inevitably more upbeat). Also, each drummer is paired with a different bass player, Jones with Steve Davis and Haynes with Jimmy Garrison. These are significant variables, not to be overlooked.

Example 1 — Elvin Jones

The awesome Elvin Jones via elvinjones.net

The round subtleness of Elvin Jones’s swing is iconic. As you listen, pay attention, however, to the delicate dance of his sticks on the ride cymbal and snare drum. This delicacy allows Coltrane’s saxophone to claim the foreground.

The drumming starts to open slightly around the 2:00 mark, more so after the 8:00 mark. But as the swing deepens and the sticks and pedals dance more, the texture remains nuanced, especially because the constancy of the ride cymbal. The texture is wonderfully silken time, and because it doesn’t snag our ears, the drumming allows the listeners ample cognitive space to absorb the solos by Coltrane and pianist McCoy Tyner.

Compare that with . . .

Example 2 — Roy Haynes

This second recording was a live recording and made almost three years after the first. It’s also faster. These facts may largely account for the aggressiveness of this second performance.

Nevertheless, where Elvin Jones’s timekeeping in the first recording is distinguished by the silken dance of the sticks on the ride cymbal and snare, Roy Haynes splashes the time around his entire drum kit. He disrupts, leaves holes, creates enjambments, and sends the groove tumbling over itself. The time keeps moving at tempo, but each turn of the wheel emphasizes a different moment within the bar.

In fact, forget the wheel; it’s as if the time keeps breaking over itself like a wave. The rough and tumble texture of the time gives Coltrane something to fight against. It feels as if we are watching him surf to shore, crashing through the water, swallowed by a wave and then miraculously resurfacing, swallowed again and then reemerging.

A final thought about this second recording. Like Elvin Jones, Haynes is a master of shaping time. Those who thrill at the busyness of his splashes around the drums without noticing the superb shape of his swing are missing something essential. Consider how difficult it is to do all of this splashing and yet drive the groove so strongly. As is often the case with drummers, his mastery is hidden in plain sight.

The unstoppable Roy Haynes, via drummagazine.com

Thank you for reading.